A little coin appears in Seven Noble Knights, once Mudarra has been in Castile for a while. He wants to give money where it wouldn't be seemly, so he mitigates his crime by casting a few obolos into the street. Described as parchment-thin and barely worth enough to buy a loaf of bread, Mudarra's coins are based on something I have in my possession.

I got this little coin on Ebay (what can't you get there?) for little money ten years ago. The vendor told me it was from the reign of Alfonso X el Sabio, pretty much my only reason for being alive at the time, so I couldn't resist. I was later able to verify in a museum in Burgos that this is just like other obolos out there, so I feel pretty confident that it's the real deal.

The front shows a castle, the emblem of Castile, and the Latin letters CASTELLE.

The back shows the lion of León and bears the inscription LEGIONIS.

Of course, Mudarra couldn't have thrown a coin that bore the emblems of both kingdoms because he lived during a time when Castile was an independent county officially still part of León. It's still likely obolos were struck at the time because of the eternal need for very small values of coins. Aside from the thinness and small circumference, one mark of a coin of small worth is that it hasn't been cut to make even smaller values. Most important to me as the author, this coin was minted during the reign of my favorite king in the history of the world and the same king whose team compiled the books where we find the first traces of Mudarra's story.

This coin weighs almost nothing, but I can feel the seven hundred years in the patina. It brings me that much closer to the realities of the lives of my characters.

Happy holidays! See you again from my new home in the new year.

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

The Cutting Room Floor

|

| Doña Lambra wonders why I cut her intro chapter. |

I always called it Chapter II because I knew the first chapter had to be much more exciting. Because it's the first piece of historical fiction I ever wrote, it has a hesitancy about it. You can almost feel me reaching out my senses and trying to describe what I thought it was like to live in Northern Spain in the year 974. It contains a lot of context and sympathizes deeply with Doña Lambra, which caused problems in my critique group later when her true nature was revealed. When I finished the first draft of the novel, I excised the first half, with the silk vendor, and eventually the second half became attached to the latest version of Chapter I. Now, the battle in the first chapter cuts directly to the wedding preparations in the former Chapter III.

Anyway, I've done my duty and killed my darling and now I lay its body out for you to view. RIP, Chapter II. (To cheer yourself up, you can watch the trailer!)

Chapter II

…una duenna de muy grand guisa, et era natural de

Burueva, et prima cormana del conde Garçi Fernández, et dizienle donna Llambla. (I put an excerpt from the Estoria de Espanna, thirteenth-century text at the head of each chapter in the first draft. This introduces Lambra, just like the chapter does in more detail.)

The sun began to relent from

its long day’s punishment of the estate of Busto de Bureba. The fish in the

river sought out the barely forming shadows cast by stones and branches. Inside

a stone house, under a thatched roof, twenty maidservants and their lady

cleaned up the dinner table, planned a cool evening meal, brought in the

washing, and put away the day’s sewing without bumping into each other.

Doña Lambra looked out the open door

when she heard a tinkling of bells on the road.

“Good evening, my lady!” cried the

peddler, halting his donkey in the middle of the road directly in front of her

house.

“What are you selling there?” Doña

Lambra wiped her brow, lifted her apron, and headed toward the packs on the

donkey’s back.

“I’m not really selling anything yet.

I’m on my way to France, where I can get the best price for these Moorish silks

and finery. But I might bring myself to part with something for the sake of one

so obviously noble.”

Lambra stood a little straighter and

felt the heavy wool dress scratch her shoulders through the wicked moisture.

She tossed her head and her flaxen braids leapt up before they reached her

waist again. “Well, I won’t buy anything before I see it.”

“Of course not, lady.”

He reached high and opened the nearest

bag’s latch. The lid popped open with the force of the tightly packed fabrics

inside. “This one on top is probably the best I have.” He pulled on a corner of

the silk and Lambra quickly appraised its luster and smoothness.

“Green?” she said.

“Don’t turn up your nose at it, my

lady. It’s the most popular color in the very caliph’s harem in Córdoba. It’s

sure to become the highest fashion, especially if other ladies see you wearing

it.”

“Sell it to the French ladies. I’ll

have no pagan colors.”

The peddler tugged at a corner of the

bolt underneath the green and a mass of azure slid into view with a swooshing

sound. He came rather closer than Lambra would have liked and held it under her

chin. “Just as I thought! A perfect match for your eyes! Or even the

Mediterranean Sea.”

“My eyes aren’t blue,” she said,

backing away.

“They certainly are! I must have a

looking glass in here somewhere.” He rummaged through three different packs.

The donkey flicked his tail and made the bells jingle. Doña Lambra tried to

imagine the peddler all alone leading his donkey, loaded high with goods, through

the rocky terrain toward France.

“Are you going through the Roncesvalles

Pass unaccompanied and with bells?”

“Just my donkey and me,” he replied.

“And the bells.”

“You should really pack the bells away

before you get into the Basque country. You have no reason to announce your

presence among those savages.”

He held a piece of polished metal

between his thumb and forefinger up to Lambra’s eyes for her to see. “I’ve

traveled through the Pyrenees many times. Don’t you think that blue silk favors

you?”

“Now, how could I possibly tell whether

the fabric favors me in such a tiny glass?” she said, taking the glass from

him. “I can’t see myself and the silk at the same time!”

He considered the fabric, eyed the pack

it had come from, and in a great sweeping motion, pulled his dinner knife from

his belt and slashed off a square of the silk. He handed it to Lambra and

folded the rest of the bolt away, saying, “You see? A perfect match. You could

embroider that swatch with your golden hairs and no one would know it wasn’t

straight from a treasure chest.”

She held the fabric under her eye and

glimpsed two blue shapes in the glass. Maybe it was just the sky. She looked

up, and the peddler had already fastened all the packs. “A gift from one so

humble to one so haughty,” he said.

“Thank you,” she mumbled, handing back

the looking glass.

He stuffed it into a pocket and tugged

at the donkey’s bridle.

Doña Lambra turned back toward the

door, where she noticed five faces of her maids disperse like a puff of smoke.

She sat on the stone bench under the eaves of her house and watched the peddler

jingle his slow way toward the mountains. She was glad he hadn’t pressured her

to buy, because she had nothing to give in trade for silks. She had

administered all her own land since her father had passed away five years

earlier, so she knew that maintaining so much land and so many people often

meant sacrifice and frugality before fashion. She picked up the end of her

braid and set it against the fabric. Yes, her hair almost could pass for gold

thread. Maybe she could have one of the girls embroider stars and moons on the

fabric and set it into a bodice. Everyone at mass would think she was wearing

the latest plunder from Andalusia, perhaps a gift from another admiring knight.

Her maids’ voices floated out the

doorway on some farmer’s melody. Always gossiping, joking, and laughing when

they thought she couldn’t hear. Well, she’d make them work hard enough

tomorrow.

An eagle shrieked across the sky in

search of prey. Lambra looked down the road to the west. What could that be?

This road was becoming a regular thoroughfare. Two knights in chainmail headed

up a twenty-man retinue, all on horseback. As they neared the house, one of the

two front men lifted up the standard, a castle on a white field.

Doña Lambra tucked the blue square into

her neckline, gathered up her skirts, and ran through her front door shouting.

“My cousin’s here! He’s got twenty knights with him! What were we having for

supper? How much wine is there?”

All the ladies dropped what they were

doing and scurried to their preassigned tasks for just such an occasion:

cutting more old bread for plates, clearing out the sides of the hall for

sleeping space. Only Justa, who had been born into the household at nearly the

same time as doña Lambra, followed alongside her lady as she charged through

the great room to the kitchen at the far end.

“You told us to just make a salad:

cucumbers, radishes, garlic, some nuts, maybe some quince jelly.”

“No garlic!” Lambra didn’t acknowledge

Justa, whose words were merely an embodiment of her own thoughts. “No garlic!”

She seized the cloves from the table where the cook was about to chop them and

threw them on the floor, where a couple of puppies began to roll them around

the packed earth and straw. “No garlic for the Count of Castile! Isn’t there

any pepper left at all? Why didn’t he send ahead so we could get some quail or

slaughter some hens? Justa! Send the boys for rabbits!” Justa ducked out the

side door. “What about the pepper?”

The cook replied, “There’s about a

spoonful left, my lady.”

“Stew the rabbits in the vinegar and

put the pepper on at the last minute so it’s still fresh and pungent at the

table. I’ll trust you to find some cheese to go with the quince, and for the

love of God, make more salad!”

The cook tried not to sweat into the

stew pot where she set some water to boil and chopped cucumbers as fast as she

could. Lambra strode back across the house and paused just inside the front

door to inhale and exhale deeply. She smoothed the hair at her temples and

stepped outside.

The retinue was already arriving at the

house. Lambra saw the Count of Castile in the center, also dressed in mail. His

undoubtedly hot and blinding helmet was secured to the back of his horse’s

saddle. Resting his hand gently on it, he dismounted in one easy motion. Lambra

started toward him, exclaiming, “Cousin García! What fortunate wind brings you

here?”

“Now, now, cousin,” he replied, taking

her into an embrace, “you know better than to address me like that. It’s been

four years now.”

“I’m sorry, your grace, most high and

noble Count, leader of all Castile!” She comically bowed from the waist to

restore some fragment of their playful childhood.

“You’re forgiven, my shrewd cousin!” He

chuckled and laid his hand on the top of her head as if in blessing.

She stood and looped her arm through

his to seal the intimacy. The other knights had dismounted, so she said, “Let

us lead your noble retinue to the stables to care for their fine steeds.” She

deliberately bypassed the door and in hopes that the extra time would allow her

maidens to make the hall look as if it were always sparkling clean and ready

for important visitors. Maybe by the time they went inside, the boys would have

brought and cleaned the rabbits and the male laborers would have arrived to

welcome the masculine retinue more appropriately than her maids could.

The Count unsaddled, brushed, and fed

his own horse. Lambra couldn’t help but wait for him outside by the river in

the cooling breezes. She let the reeds brush against her hands while she

inhaled the wet river fragrance mixed with summer blossoms. The eagle cruised

across the darkening sky toward its nest.

Her cousin came out to meet her by

himself. “I’ve sent the men inside. I have to tell you why I’m here, Lambra,

and this might be the best place for it.”

She took his outstretched hand and

noticed the way he avoided her gaze. “What can it be?”

“Lambra, you’re such a beautiful woman,

and so rich in lands, I can’t think of any man who truly deserves you!”

She squeezed his slippery hand.

“Cousin, has something happened to your wife?” Did he want to marry doña

Lambra?

He smiled and looked at her. “She’s

very well. She’s in Burgos, expecting our second child.”

“That’s wonderful. Praise be to God!”

García looked away again and stared

into the sun as it eased below the mountains. “You may have heard about the

happy conclusion of the siege of Zamora.”

“Oh, yes! We were all so glad to hear

that that beautiful city remains within Castile.”

“Well, Zamora is more of a border

outpost than Burgos, or even Bustos de Bureba, but I suppose it has its charms.

A good river, and it’s strategic for keeping the Kingdom of León in check… But

did the news come with the reason for the end of that interminable siege?”

“There was a name, someone I’d never

heard of, from far away.”

“Ruy Blásquez. Ruy Blásquez saved the

city of Zamora. I would still be there today if he hadn’t come to my rescue.”

Doña Lambra thought the Earth shifted

beneath her as she realized what was really happening. She was being given

away. Married off, passed from hand to hand as if she had nothing better to do,

as if Bureba could get by without her.

Doña Lambra had not expected to be

given in marriage. With both of her parents already passed into the next world,

she had been raised principally by dueñas and other servants who could

wield no real authority over her. Now well into puberty, she had been taking

inventory of all the surrounding noblemen, deciding which lands she might like

to administer, so as to arrange her own nuptials. It even occurred to her that

she needn't marry at all, but simply govern her own holdings until such time as

her Father in Heaven saw fit to pass them on to his Holy Church.

But she was nothing if not shrewd, and

if she had considered it, she would have realized that as the cousin of García

Fernández, the Count of Castile, she would likely end up as a reward to one of

his loyal warriors.

“Some vassal rescued you? I should

think he was merely doing his duty.”

“Oh, Lambra, you can have no idea how

far above the call of duty he went. He brought one thousand knights and united

them all under Castile’s standard. And now we can fly that flag over Zamora! I

know you don’t know any other way for things to be, but it was only my father

Fernán González – less than a generation ago! – who declared Castilian

independence from León and it’s far from a consolidated reality. By bringing so

many to rally for our country, Ruy Blásquez has made himself my most valuable

vassal. And so, when he asked me to find him a wife, naturally I thought of

you, the richest and most noble of all my relatives.”

Doña Lambra let the orange and gold

rays spewing from behind the mountain burn her eyes. “But who is this Ruy

Blásquez? How old is he?”

“He’s well established.” The Count

walked around and tried to face his cousin, but she turned away from him every

time. “He’s completed his thirty-fifth year.”

She couldn’t help but wring her hands

at the thought of a grey beard and rotting teeth. Well, but maybe he wouldn’t

live that long, then she would administer all the territory they had between

them.

“Is he landed?”

“He has a few parcels in the region of Lara, called

Vilviestre.”

“A few parcels? I am the lady,

practically the countess, of all of Bureba! Thousands of landholders owe their

fealty to me and no one else!”

“Thousands? Hundreds, perhaps.”

“Thousands!”

“Lady, you forget yourself. We may be

cousins, but I am the Count here. All of ‘your’ vassals ultimately work for

me.”

Her eyes found his, but he had to look

away. She bowed her head and whispered, “Lara’s so far. I never imagined going

so far.”

He caught her as she collapsed,

sobbing.

García entered the house first. As

Lambra’s eyes adjusted to the firelight, she saw all of her people seated on one

side of the great table, knives out, bread trenchers in front of them, with the

Count’s men seated on the other side. They had wisely left the head of the

table unoccupied for the Count and the lady of the house. She wiped her eyes

one last time. “Pour the wine!” she said a little too loudly. “We have much to

celebrate! I’m to be wed this year!”

Thursday, November 7, 2013

Entertaining, Fast and Fun Trailer Debut

I've been working on this for about six months now. It's more of a pitch than a trailer, simply because the book isn't published yet. I hope it's entertaining and makes you interested in the story. Please let me know!

I couldn't have accomplished this by myself.

The talented graphic novelist or "story artist" Ayal Pinkus did the drawing and painting that makes this trailer so special. I can never thank him enough for lending his talent to bringing the Seven Noble Knights to life. It's incredible to see the characters and events that have so far only been words on pages or screens this much closer to flesh and blood. Our collaboration was amazingly fruitful.

The professional voiceover was done by James Scott.

The background music was chosen after much agonizing. It's "Non me mordas, ya habibi" (Don't Bite Me, oh Lover), a jarcha from medieval Andalusia. The text is written in a proto-Spanish that has a strong relationship to what the characters in Seven Noble Knights would have been speaking, and when he goes to Córdoba, Don Gonzalo hears a similar jarcha. This version is performed by the Eduardo Paniagua Ensemble Música Antigua and is available on the album El crisol del tiempo.

Thanks so much for watching. If you feel inclined to do me a favor, watch it many more times — as many as you can — and share it with any of your friends interested in historical fiction. Thank you!

I couldn't have accomplished this by myself.

The talented graphic novelist or "story artist" Ayal Pinkus did the drawing and painting that makes this trailer so special. I can never thank him enough for lending his talent to bringing the Seven Noble Knights to life. It's incredible to see the characters and events that have so far only been words on pages or screens this much closer to flesh and blood. Our collaboration was amazingly fruitful.

The professional voiceover was done by James Scott.

The background music was chosen after much agonizing. It's "Non me mordas, ya habibi" (Don't Bite Me, oh Lover), a jarcha from medieval Andalusia. The text is written in a proto-Spanish that has a strong relationship to what the characters in Seven Noble Knights would have been speaking, and when he goes to Córdoba, Don Gonzalo hears a similar jarcha. This version is performed by the Eduardo Paniagua Ensemble Música Antigua and is available on the album El crisol del tiempo.

Thanks so much for watching. If you feel inclined to do me a favor, watch it many more times — as many as you can — and share it with any of your friends interested in historical fiction. Thank you!

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Touching the Past

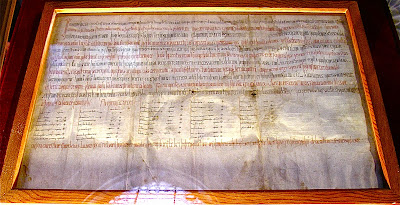

I was going through some photos I took when I was in Burgos in October 2005 and was thrilled to find this gem:

It's a document granting Covarrubias to a noble monastery. It's signed by Count García Fernández, supreme leader of Castile and a character in SNKL. His wife Ava also signs. She isn't a character in SNKL, but a strong possibility for a sequel. The document dates from 972, ever so close to the year SNKL opens.

This wonderful piece of faded, wrinkled, and water damaged vellum was on display in the cathedral, under glass, and you can see the reflection from the window in the picture. At the time, I was impressed with the undulated Visigothic majuscule writing and the sheer age of the document. Could I have known that seven years later, having finished the dissertation I was researching, I would complete the biggest, most complex piece of writing of my entire life about the very time period when this document was made and one of the very people who signed it?

Now that I've written SNKL, I find myself wishing I could tell my 2005 self to take even more pictures and look even more closely at these extraordinary objects I haven't had the chance to get so close to since then. In that way, 2005 seems farther away from me than even the year 972.

In other news, the artist completed scanning all the pictures for the SNKL trailer, so keep an eye out for that. It's going to be great!

It's a document granting Covarrubias to a noble monastery. It's signed by Count García Fernández, supreme leader of Castile and a character in SNKL. His wife Ava also signs. She isn't a character in SNKL, but a strong possibility for a sequel. The document dates from 972, ever so close to the year SNKL opens.

This wonderful piece of faded, wrinkled, and water damaged vellum was on display in the cathedral, under glass, and you can see the reflection from the window in the picture. At the time, I was impressed with the undulated Visigothic majuscule writing and the sheer age of the document. Could I have known that seven years later, having finished the dissertation I was researching, I would complete the biggest, most complex piece of writing of my entire life about the very time period when this document was made and one of the very people who signed it?

Now that I've written SNKL, I find myself wishing I could tell my 2005 self to take even more pictures and look even more closely at these extraordinary objects I haven't had the chance to get so close to since then. In that way, 2005 seems farther away from me than even the year 972.

In other news, the artist completed scanning all the pictures for the SNKL trailer, so keep an eye out for that. It's going to be great!

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Catchphrases and the Title

Because I haven't yet encountered the enthusiastic support from New York every writer dreams of, I've been thinking about what I can do to give The Seven Noble Knights of Lara that X factor.

In the first draft of my query, I had a major attention-getter in the opening line: "The Seven Noble Knights of Lara is a medieval epic with strong women, valiant knights, and a bloody cucumber." It even made it into a radio clip when I presented it at the Book Doctors' Pitchapalooza in Naperville! It garnered laughter at the time, and there are a couple of problems with that: I wasn't sure whether it was funny laughter or uncomfortable laughter, and the book itself isn't intended to be a laugh fest. I kept it for a while, thinking that any attention I can grab is good attention, but eventually I felt too strongly that I was setting up false expectations, and changed it.

The first way I made it less comical was to remove the rule of three: "The Seven Noble Knights of Lara has strong women and valiant knights. It is probably the only novel you'll ever read with a bloody cucumber." (This version is up on the "About the Novel" page and will come down soon.) I got at lot of approval for this arrangement, but eventually, also some puzzlement. Why do I think anyone would necessarily be attracted to a novel with a bloody cucumber?

I'm trying! I really am. So I took that version out, too. My query letter now has no real "logline." It launches right into the "When Gonzalo does one thing, Lambra does another" plotting. I felt the loss of the logline and decided to try to remedy it. I came up with the logline in the picture above.

Not making giant leaps of progress away from humor, am I? I'd like to invite my readers to help me write a logline that conveys more of the feel of the book, which tends toward the dramatic. Not the melodramatic! Please comment or contact me on Facebook or Twitter if you have good ideas.

In the meantime, I like the picture above and may use it and its logline.

So, no logline. How about the title? Is it too long? Too boring? I'm willing to admit I haven't been creative with the title. I just translated the title academics have assigned to the epic poem. If it helps the book, I'll change it. But to what? Would THE FAULTS OF OTHERS work? If not, I'm afraid I'll lapse into the unintentionally comical, such as BLOOD IN BURGOS or CRESCENT OVER CÓRDOBA.

The trick is to be concise and impactful without dipping into the flippancy that seems to surface in me whenever I try to write in such a short form.

I look forward to hearing from you!

In the first draft of my query, I had a major attention-getter in the opening line: "The Seven Noble Knights of Lara is a medieval epic with strong women, valiant knights, and a bloody cucumber." It even made it into a radio clip when I presented it at the Book Doctors' Pitchapalooza in Naperville! It garnered laughter at the time, and there are a couple of problems with that: I wasn't sure whether it was funny laughter or uncomfortable laughter, and the book itself isn't intended to be a laugh fest. I kept it for a while, thinking that any attention I can grab is good attention, but eventually I felt too strongly that I was setting up false expectations, and changed it.

The first way I made it less comical was to remove the rule of three: "The Seven Noble Knights of Lara has strong women and valiant knights. It is probably the only novel you'll ever read with a bloody cucumber." (This version is up on the "About the Novel" page and will come down soon.) I got at lot of approval for this arrangement, but eventually, also some puzzlement. Why do I think anyone would necessarily be attracted to a novel with a bloody cucumber?

I'm trying! I really am. So I took that version out, too. My query letter now has no real "logline." It launches right into the "When Gonzalo does one thing, Lambra does another" plotting. I felt the loss of the logline and decided to try to remedy it. I came up with the logline in the picture above.

Not making giant leaps of progress away from humor, am I? I'd like to invite my readers to help me write a logline that conveys more of the feel of the book, which tends toward the dramatic. Not the melodramatic! Please comment or contact me on Facebook or Twitter if you have good ideas.

In the meantime, I like the picture above and may use it and its logline.

So, no logline. How about the title? Is it too long? Too boring? I'm willing to admit I haven't been creative with the title. I just translated the title academics have assigned to the epic poem. If it helps the book, I'll change it. But to what? Would THE FAULTS OF OTHERS work? If not, I'm afraid I'll lapse into the unintentionally comical, such as BLOOD IN BURGOS or CRESCENT OVER CÓRDOBA.

The trick is to be concise and impactful without dipping into the flippancy that seems to surface in me whenever I try to write in such a short form.

I look forward to hearing from you!

Monday, September 23, 2013

Medieval Spanish Names II

In the last post, I lamented the lack of imagination medieval Spaniards displayed when it came to naming their male children. Some of that current also arises in female names. I think Toda and Mayor (sounds something like "my oar") are related to earlier Roman or Celtic naming habits, because Toda could refer to the girl being an only child and Mayor indicates she's the eldest.

Otherwise, the historical record is full of names that have survived into the present day, like Teresa, María, and Juana. Much more exciting to find are the ones that haven't had much impact on the present day, such as

There was a Queen Urraca of Castile for a while who deserves several novels, and another Urraca has a role in one of the historicals I'm researching now. Best of all, "urraca" is the modern Spanish name for the magpie, a bird I have always found mysteriously breathtaking.

In the course of that research, I found out something disturbing about one of of my main female characters: I'd been calling her the wrong name the entire time! Gonzalo Gustioz's wife Sancha, so called in the histories and poems, went on the record in charters and donations with the name Prollina.

I was disappointed because the next book I want to write has a main character also named Sancha, and if I could have used a different name for the SNKL Sancha, it would be less confusing all around.

But then I got thinking why the poets changed the name. Sancha means "holy" or "saintly," which is perfect for this long-suffering mother of seven warrior sons. And Prollina, no offense, isn't very pretty. Storyteller's prerogative strikes again!

Otherwise, the historical record is full of names that have survived into the present day, like Teresa, María, and Juana. Much more exciting to find are the ones that haven't had much impact on the present day, such as

Tigridia

Fronilde

Argelo

Eylo

Goda

Gontroda

Flammula ("little flame," quickly morphed into "Lambra," the villainess of SNKL)

and my all time favorite, Urraca

There was a Queen Urraca of Castile for a while who deserves several novels, and another Urraca has a role in one of the historicals I'm researching now. Best of all, "urraca" is the modern Spanish name for the magpie, a bird I have always found mysteriously breathtaking.

In the course of that research, I found out something disturbing about one of of my main female characters: I'd been calling her the wrong name the entire time! Gonzalo Gustioz's wife Sancha, so called in the histories and poems, went on the record in charters and donations with the name Prollina.

I was disappointed because the next book I want to write has a main character also named Sancha, and if I could have used a different name for the SNKL Sancha, it would be less confusing all around.

But then I got thinking why the poets changed the name. Sancha means "holy" or "saintly," which is perfect for this long-suffering mother of seven warrior sons. And Prollina, no offense, isn't very pretty. Storyteller's prerogative strikes again!

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Medieval Spanish Names I

|

| A dismayed young Gonzalo is comforted by his mother, Sancha, in the upcoming trailer. |

Two of the most important protagonists of SNKL are Gonzalo Gustioz and his son, Gonzalo González. Those are the names they either had in history or were chosen for them by the wise and gentle medieval jongleurs and historians. Faced with this identity crisis, I agonized over what to do. I was afraid the text would get confusing and off-putting.

In the end, I left the names as I found them and used convenient cues to make certain the reader knew which Gonzalo I was writing about: the father gets the title "Don," even though the son is also a knight, and the son often gets the descriptor "young" before his name. I also kept the nickname Gonzalico strictly for the son. It turned out that the father and son don't spend much time in the same scenes, so once I'd established point of view (because they're so strong, they pretty much call the shots in their respective chapters), I could drop the shorthand clues. For example, in Chapter VII, everyone knows I'm talking about Gonzalo the son, because the father is off on a journey he started in the last chapter.

I could always tell the difference between them, which seems to mean readers can, too. I never got a single complaint about the issue before this one.

It points out a challenge in writing historical fiction about medieval Spain: the lack of distinctive names. I think one reason the old texts always refer to the villain by the full name, Ruy Blásquez, is not only to establish psychic distance, but also because the listeners in the first audience would have appreciated knowing which Ruy the singer meant among all the Ruys in all the histories and among their acquaintances. Spanish parents in the tenth century displayed a lack of creativity in naming their children, giving rise to the use of patronymics, place names, and, one presumes, nicknames that haven't survived very often in the historical record. And more than one pulled-out hair among historical fiction authors. And possibly more than one opportunity for the same authors to take their own creative license.

To be continued with women's names...

Monday, August 19, 2013

Picture It!

|

| Gonzalo and Álvar have a difference of opinion. |

I came up with a lot of ideas under the philosophy of "Dream Big." None of them were practical, at least not with my current resources. (My life changes drastically in that regard every six months or so.) However, an idea's impracticality doesn't mean I forget about it, so I held onto the idea of an unusual book trailer for a month or two. Then, through the vicissitudes of life, I virtually met graphic novelist Ayal Pinkus, and made creative use of this new talent in my life by asking if he'd like to illustrate the first third of The Seven Noble Knights of Lara.

He said he would!

We've been having a great time ever since, bouncing ideas off each other and off the walls, trading historical pictures back and forth, and generally being creative. The process has helped me think about the novel in new ways, which I hope will benefit both my search for representation and my readers. So hang in there! It's coming, and it's going to be great!

For the color scheme, we settled on primary shades, but using tints they might have had available for clothing dye in the year 974. The result, I think, shows the expensive colors everyone wanted to display with just a slight historical patina. And it really intensifies the drama.

|

| Setting the scene: Burgos, 974. A wooden castle has just been destroyed by competing knights during the festivities at the wedding of Ruy Blásquez and Doña Lambra. |

Monday, August 5, 2013

The Epic Poem, the Novel, and History

The Seven Noble Knights of Lara is based on Los siete infantes de Lara or de Salas, an episode of Spanish history tied up in poetry and heroism. It is a story full of violent passions and old-fashioned revenge. It hits such an unusually fevered pitch that some scholars believe the story must have originated in the epic tradition of northern Europe. It might have traveled to Spain through royal marriages during the thirteenth century. In spite of the differences between this epic and other Spanish stories, The Seven Noble Knights of Lara displays a typically Spanish obsession with geography and treats specifically Spanish themes, such as coexistence and wars with the Islamic governors of Andalusia and the supremacy of Castile among the Christian kingdoms.

None of the poetry of the original epic — if it ever existed — has survived to the present day. In the thirteenth century, King Alfonso X el Sabio had his scholars compile a history of Spain from the beginning of time to their present day, and they recorded the episode of Los siete infantes de Lara over the course of several chapters taking place during the rule of the second Count of Castile, García Fernández, in the late tenth century. In the twentieth century, scholars noticed that in several places, this supposedly historical text rhymed and presented meter and repetition typical of epic poetry. Some of the stanzas have been reconstructed, but the closest we can get to the entire original story is through the prosified version and later medieval histories.

Whether the incident represents historical facts has always been up for debate. The possibility that the medieval historians derived it from an epic poem does not argue for or against its truthfulness, as traveling minstrels or jongleurs would have been the main source of news at the time, and they could remember the facts more easily when it followed a familiar format (and rhymed).

Two fantastical elements in the story argue against the historical nature of the tale, but they can also be interpreted as miracles — confirmations of God's glory in everyday life — which medieval people would have taken as utterly factual and believable.

The first miraculous event concerns a ring which has been split in two, and the pieces separated in distance and time. As in other folk tales, when the two halves meet again, they magically fuse, never again to be sundered. Whether because it was considered a miracle, or they thought magic was more prevalent a few hundred years before, or they just weren't that concerned with details, the medieval historians record this without comment. I knew today's readers wouldn't swallow the magical reunion of the ring's halves without question, so in my novel, I simply had the ring melded back together in a normal forge.

The second fantastical occurrence concerns Don Gonzalo's eyesight. He goes blind with weeping over the years Salas is in ruins, and when his fortunes change, his sight miraculously returns. I'm sure it's more metaphorical than a strict plot point, but I recognized this as an opportunity to give the reader an experience of the medical practices of the day. Physicians were doing successful eye surgery in the Arab world at this time, so in my novel, Don Gonzalo develops sudden cataracts from weeping, staring into the sun, and even a swift kick in the face. Later, I go into the gory details of cataract surgery with an Andalusian doctor. The method is still performed the same way in developing countries today. The scene also serves to emotionally bond some of the characters.

Author Kim Rendfeld called this passage "riveting." I couldn't be more pleased with the results of my efforts to reconcile the fiction and the historically believable in my little epic.

The first miraculous event concerns a ring which has been split in two, and the pieces separated in distance and time. As in other folk tales, when the two halves meet again, they magically fuse, never again to be sundered. Whether because it was considered a miracle, or they thought magic was more prevalent a few hundred years before, or they just weren't that concerned with details, the medieval historians record this without comment. I knew today's readers wouldn't swallow the magical reunion of the ring's halves without question, so in my novel, I simply had the ring melded back together in a normal forge.

The second fantastical occurrence concerns Don Gonzalo's eyesight. He goes blind with weeping over the years Salas is in ruins, and when his fortunes change, his sight miraculously returns. I'm sure it's more metaphorical than a strict plot point, but I recognized this as an opportunity to give the reader an experience of the medical practices of the day. Physicians were doing successful eye surgery in the Arab world at this time, so in my novel, Don Gonzalo develops sudden cataracts from weeping, staring into the sun, and even a swift kick in the face. Later, I go into the gory details of cataract surgery with an Andalusian doctor. The method is still performed the same way in developing countries today. The scene also serves to emotionally bond some of the characters.

Author Kim Rendfeld called this passage "riveting." I couldn't be more pleased with the results of my efforts to reconcile the fiction and the historically believable in my little epic.

Monday, July 22, 2013

Characters: Gonzalo González

I'd like to introduce the most important member of the title characters via an excerpt. From Chapter II, this is the first time we see the title characters, and Gonzalo in particular. The scene takes place on the banks of the Arlanzón River in Burgos, Spain, in the year 974. A proud mother introduces her sons to her soon-to-be sister-in-law and her servants. I'll put all clippings from the novel on the new Excerpts page.

|

| Eduardo Verastegui. This is how handsome (and Spanish) Gonzalo should look. |

Sancha’s face lit up again. “My sons are outside with my husband, waiting to meet you.” She grasped Doña Lambra’s limp hand and pulled her outside.

Justa, Gotina, and all the other servants followed the count and Álvar Sánchez outside to find a concentration of masculinity so intense, Justa could feel it wash over her like the waves of the Cantabrian Sea. Nine men, each with a gleaming sword in his belt, and seven with dark brown hair that shone bronze in the sunlight, laughed and talked amongst themselves, producing a resonant rumble in the women’s ears.

Count García said playfully, “Hey, Gonzalo, come and meet your future relative, and bring those sons of yours. Ah, there they are! I would never have known, since they’re so quiet.”

[All six of Gonzalo's elder brothers briefly meet with Lambra, and then we come to the youngest.]

“That will do, Gustio,” cut in Doña Sancha. She took Doña Lambra’s hand and patted it warmly. “And this is my youngest, Gonzalo. We call him Gonzalico.”

The knight in question grimaced at his mother, but just as quickly flashed a smile at Doña Lambra and Justa. He looked to have completed about fifteen years, just like Doña Lambra. Even in similar clothing and with the same nearly black hair and athletic build as his brothers, he was unique. Passersby, whether men or women, let their gazes linger on him. Behind his eyes danced a playful spirit, but it was impossible to tell whether it was angel or demon. Justa observed that the air around Gonzalo seemed to move faster, to bounce off his skin and radiate outward in jagged waves. Her heart skipped. Perhaps this nephew could be an exciting friend for her lady.

Doña Lambra held out her hand for a kiss and was absorbed into his energy. She seemed to pull away as quickly as she could.

The other brothers gathered around, eager to tell Doña Lambra about their little brother.

“Gonzalo’s learning about law. I often consult him when cases come before me,” said Diego, the eldest.

“He’s good at everything he tries,” said Gustio.

Suero added, “He’s even a decent hunter when I lend him my goshawk.”

“Your goshawk?” young Gonzalo shrilled. “You’re just lucky I let you hold him sometimes.”

“Now, boys,” Doña Sancha said over their boisterous teasing. “Let’s act like the nobles we are.”

Justa looked at Doña Sancha and tried to imagine all those well-formed men coming out of her somehow.

Monday, June 24, 2013

Characters: Blanca Flor

There are several characters in SNKL who began as a throwaway phrase in the source material. Yusuf came about because Mudarra needed a guide through Christian Spain, and Justa blossomed out of Doña Lambra having "a single maid" at one point in the story. They both took on their own amazing (in my opinion, because they seemed to develop independent of my original intent) story arcs.

Blanca Flor, however, is all mine. I took her name from other medieval epics and her personality from the question: What would Doña Lambra and Ruy Blásquez's daughter have been like? The epic states that they had no issue, but what if the case was more that after the terrible things their parents did, no one wanted to be associated with them, especially by blood ties? If I do write a sequel to SNKL, it will be based largely on that tension.

Personally, when I think of a female between 14 and 25 years old, I don't see a fully grown woman, but in the tenth century, people did in general. We're coming full circle with the way teenagers dress and make themselves up these days, but that's another story. So I took inspiration for Blanca Flor's look from her mother, seen in this post, and in this gorgeous artist's fantasy:

Then I made a sketch with words to evoke when I described her for the first time. Hard to see pencil in the scan, but here it is:

I was going for the beauty of the mother, but full of kindness.

Here's how the description ended up, from the point of view of Mudarra:

He ducked behind the tree trunk, from where he observed a being who radiated so much brightness he hardly dared to keep watching her, and yet he couldn’t look away. As he stared, he distinguished two long braids the color of gold thread that pulled the hood from her head and whipped from side to side and front to back as the girl-woman changed her gait to suit her mood. Her mantle flew away from her body with each step like the wings of a giant bird taking flight. At her neck, an underdress of a fine, almost transparent fabric protected her fair skin from the blue wool of her tunic. The skirt, covered in embroidered whorls, danced stiffly atop soft leather boots. Mudarra thought he would visit a cobbler and have similar boots made for himself in a strangely practical thought that ran somewhere below the rapturous feelings the female caused in him. She distractedly passed the empty bucket from one soft-looking mitten to the other as she made her meandering way toward the riverbank. He had never laid eyes on anything like her.

Blanca Flor, however, is all mine. I took her name from other medieval epics and her personality from the question: What would Doña Lambra and Ruy Blásquez's daughter have been like? The epic states that they had no issue, but what if the case was more that after the terrible things their parents did, no one wanted to be associated with them, especially by blood ties? If I do write a sequel to SNKL, it will be based largely on that tension.

Personally, when I think of a female between 14 and 25 years old, I don't see a fully grown woman, but in the tenth century, people did in general. We're coming full circle with the way teenagers dress and make themselves up these days, but that's another story. So I took inspiration for Blanca Flor's look from her mother, seen in this post, and in this gorgeous artist's fantasy:

Then I made a sketch with words to evoke when I described her for the first time. Hard to see pencil in the scan, but here it is:

I was going for the beauty of the mother, but full of kindness.

Here's how the description ended up, from the point of view of Mudarra:

He ducked behind the tree trunk, from where he observed a being who radiated so much brightness he hardly dared to keep watching her, and yet he couldn’t look away. As he stared, he distinguished two long braids the color of gold thread that pulled the hood from her head and whipped from side to side and front to back as the girl-woman changed her gait to suit her mood. Her mantle flew away from her body with each step like the wings of a giant bird taking flight. At her neck, an underdress of a fine, almost transparent fabric protected her fair skin from the blue wool of her tunic. The skirt, covered in embroidered whorls, danced stiffly atop soft leather boots. Mudarra thought he would visit a cobbler and have similar boots made for himself in a strangely practical thought that ran somewhere below the rapturous feelings the female caused in him. She distractedly passed the empty bucket from one soft-looking mitten to the other as she made her meandering way toward the riverbank. He had never laid eyes on anything like her.

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Uses of Violence

The end of a really productive three-part discussion on violence in storytelling by David Blixt comes at an a propos time in the aftermath of the Red Wedding episode of the Game of Thrones series. It's well argued -- check it out!

I've never been sure why I was so strongly drawn to the story that is the basis for The Seven Noble Knights of Lara. It's violent, and I've never enjoyed stories that showcase violence for its own sake. So, it became my mission to present the violence in a way that would affect the reader deeply at the same time that it examines the conflict from both sides and humanizes the villains. Conflict is necessary for story, and a good story will show the conflict in all its subtlety and let the reader decide what it really means.

After all, this is not a new story. It's already been told in a formulaic and psychologically vacant way, so there's no point in retelling it unless I add value in the form of sympathetic characters with believable motives and emotions.

I began by trying to understand why the woman who apparently motivated the biggest violent act in the entire book -- Doña Lambra -- was moved to such outrageous and unbecoming behavior. Because I started with her, I fell in love with her, and deeply confused my beta readers and some people who read my first attempts at query letters and a synopsis. I also loved the proper "good guys" in the book, but the fondness I had for writing about Lambra skewed readers' perceptions of the González family in the wrong direction and failed to prepare them for the meaning of the gore to come. I've done a lot of editing and hope I've ended up with a nice, complex balance of characteristics and perceptions in both camps. Anyone can write a good hero, but a good villain is the mark of the great writer I want to be.

It's an epic story and I hope I've given each character the attention he or she deserves.

So anyway, if you liked or understood or enjoyed being devastated by the Red Wedding, The Seven Noble Knights of Lara has incidents that I hope affect the reader in a markedly similar fashion.

I've never been sure why I was so strongly drawn to the story that is the basis for The Seven Noble Knights of Lara. It's violent, and I've never enjoyed stories that showcase violence for its own sake. So, it became my mission to present the violence in a way that would affect the reader deeply at the same time that it examines the conflict from both sides and humanizes the villains. Conflict is necessary for story, and a good story will show the conflict in all its subtlety and let the reader decide what it really means.

After all, this is not a new story. It's already been told in a formulaic and psychologically vacant way, so there's no point in retelling it unless I add value in the form of sympathetic characters with believable motives and emotions.

I began by trying to understand why the woman who apparently motivated the biggest violent act in the entire book -- Doña Lambra -- was moved to such outrageous and unbecoming behavior. Because I started with her, I fell in love with her, and deeply confused my beta readers and some people who read my first attempts at query letters and a synopsis. I also loved the proper "good guys" in the book, but the fondness I had for writing about Lambra skewed readers' perceptions of the González family in the wrong direction and failed to prepare them for the meaning of the gore to come. I've done a lot of editing and hope I've ended up with a nice, complex balance of characteristics and perceptions in both camps. Anyone can write a good hero, but a good villain is the mark of the great writer I want to be.

It's an epic story and I hope I've given each character the attention he or she deserves.

So anyway, if you liked or understood or enjoyed being devastated by the Red Wedding, The Seven Noble Knights of Lara has incidents that I hope affect the reader in a markedly similar fashion.

Friday, May 24, 2013

Characters: Mudarra

This guy should credibly play his father in the movie version. (Oh, yes, the role of Don Gonzalo is coming for you, Mr. Clooney!)

I could have looked online for inspiring pictures like these, but at the time, I thought it would be more creative to draw a picture myself. I've never been a particularly visual writer, so I thought that might jump-start those muscles. Sometimes the creativity only really gets flowing in one area when you take a break and try to create in another medium. I never took drawing lessons, but here's my description guide for Mudarra.

Would this make an impression on you?

Here's how the description ended up:

... how

could it be anyone else, with the same cowlick in the front of his dark, almost

black hair that pointed in every direction before curling almost tamely under

his ears? His eyes were shaded under the same wild brows, and his long,

straight nose, exactly like his father’s. His square chin supported the same

half-grown stubble of a child on the verge of becoming a man. His mouth was

pursed in seriousness, but Sancha recognized instantly its shape, always ready

to burst into a smile or laughter. ...

Where had he been all this

time? He’d been doing well. As he knelt before them, his long cloak opened to

reveal that it was lined entirely in a fur as fine as silk and much warmer than

the hole-ridden lynx pelt. The tunic he wore underneath, made of a

soft-looking, fuzzy fabric, seemed to create its own heat with its bright red

color and golden embroidery. The hand he held out to her and her husband had

golden rings embedded with shimmering carbuncles on each finger. Even his boots

were studded with beads that sparkled as much as rubies. The only detail that

seemed out of place for a well-landed lord somewhere in Andalusia or in the

borderlands was the length of rough string that secured a small pouch around

his neck.

Friday, May 10, 2013

Characters: Doña Lambra and Doña Sancha

I used these illustrations of ninth-century noble ladies as the inspiration for what Doña Lambra and Doña Sancha, the two main female characters, are wearing the first time they meet each other in Burgos before the wedding.

I colored the edges of Lambra's chain mail girdle and sleeves to appear as if they were pieces of jade in a brass setting. Her dress should probably be a richer color, as it's her best dress, inherited from her mother. I think the most inspiring element of this sketch is the haughty look in the tilt of her head and pursing of her lips.

I imagined Sancha's underdress or chainse to be made of a delicate, expensive fabric, and the tunic or bliaud to be richly colored, but with a more Hispanic type of embroidery. The mantle seems mainly practical to me, but perhaps it was once dyed a very dark color that has faded to grey with washing. I imagine her shorter than Lambra, even though she's much older, and the pleasant expression in the sketch is appropriate to the character I describe in the novel.

These come from Tom Tierney's Medieval Fashions Coloring Book. Sometimes, writing gets to be too much and you just have to color.

Cultural note: The title doña is the female equivalent of don, which is used in the same manner as English "sir." It may be used with the first name or the complete name, but not with the last name only. Derived from Latin dominus and domina, they translate more or less to "Lord" and "Lady."

Cultural note: The title doña is the female equivalent of don, which is used in the same manner as English "sir." It may be used with the first name or the complete name, but not with the last name only. Derived from Latin dominus and domina, they translate more or less to "Lord" and "Lady."

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Traitors and Turncoats: The Vile and Incomprehensible Ruy Blásquez

|

| Supposedly an illustration of an incident from the cycle of El Cid, which also comes from historical/epic tradition. |

I wanted to discuss the baddies of The Seven Noble Knights of Lara here. There are spoilers in the following comments.

The story on which I base The Seven Noble Knights of Lara contains historical figures, but the existence of Ruy Blásquez and Doña Lambra has not been verified, perhaps because no one, even today, would welcome the possibility of being associated with such vile traitors.

Ruy Blásquez –

a. k. a. Ruy Velásquez – doesn’t kill a king or even a count. But when he wipes

out seven warrior brothers in an epic battle and sends their father to be

beheaded, he eliminates an entire generation of soldiers of Castile, leaving himself

with all the power for more than ten years at the turn of the eleventh century.

The crime is all

the worse because the warriors are his nephews, the sons of his sister. There

are few stronger blood ties at this time in history. An uncle is expected to

take on an almost nurturing role, ensuring that his nephews realize their

potential, especially on the battlefield, and for this surrogate father to cut

the knights down in their prime frankly smacks of taboo. Further compounding the betrayal, Ruy

Blásquez uses an army of Moorish soldiers to take down his nephews and sends

their father to Córdoba, the capital of the Islamic caliphate. His close

association with powerful Muslims taints him in the eyes of his Christian

neighbors. His actions betray not only his blood relatives, but also the

Christian faith.

Although I tell

the story from many different points of view in my novel, Ruy Blásquez’s

actions are so hard to understand that I dared not take a seat behind his eyes.

The source material writers seem to have felt the same taboo. They make an

effort to distance the audience from Ruy Blásquez, referring to him as I do

here, always with his first and last names, and usually appending “that

traitor” or calling him simply “the traitor.” I took a more subtle route: I made

him a slippery character, hard to get a handle on in general, so that his

incomprehensibility in the betrayal is somewhat believable. The reader is left

to conjecture that his wife, Doña Lambra, made him do it.

Doña Lambra, on

the other hand, was too much fun not to try to understand. She’s frustrated

because she has to marry Ruy Blásquez and covets the nephews’ superior power.

She also feels an inconvenient level of sexual tension around her handsome new

nephews-in-law, and when they get into an argument and kill her cousin, she snaps. She

has to be a little insane to take such a disproportionate revenge, but she also

has to be manipulative or influential in order to get Ruy Blásquez to agree,

even if he is wishy-washy. It was delightful creating this dangerous beauty the

reader loves to hate.

Check back soon for more about how I developed these fascinating characters.

Monday, April 8, 2013

Big Word, Right Word

|

| The mihrab at the mezquita-catedral in Córdoba features a horseshoe arch. |

When I brought the book to my critique group, which consists of great writers who happen to lack an interest in historical novels, more often than not, they found it accessible. If there were terms or circumstances particular to tenth-century Spain, I went back and explained them enough to keep an uninitiated reader up to speed without slowing the story down. So that anxiety waned and I pounded out the rest of the book without that internal editor.

Then my husband read it. He's now working in retail, which has shaken his faith in humans' ability to rise to an occasion. He thinks some of the "big" words I use will put readers off and recommends cutting them.

The thing is, sometimes, especially in a historical context, the "big" word is the right word.

The most passionate debate came about because of a couple of architectural terms at the end of the book. Our hero notices a polylobed arch where there was none before. My husband stumbled over "polylobed" and passionately defended its execution. Do you know what a polylobed arch is? If you didn't, did the word's use in the sentence upset you?

A polylobed arch is an arch with many lobes, as seen in this picture. I don't know of any other word that would distinguish this style from other types of arches, so it must be the right word.

Normally I wouldn't put up a fight about something so small, but I want to leave this word in because earlier on the same page, the hero notices a horseshoe arch. That's also a technical term, but my husband didn't reject it because it's more intuitive. It wouldn't be easy to create the same effect without the word "polylobed": "a horseshoe arch here... and an arch over there."

The use of this word didn't bother my editor. My critique group hasn't gotten to the end of the book yet, so their jury's still out. What do you think? Is this an example of a word that's too "big"? Or is it just the right word?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)